It’s holiday season. Often, this time of year, people feel romantic. Consequently, engagements and gifts of jewelry abound. Having many people in my life become engaged and married of late, I’ve been thinking a lot about all the bling that goes along with these endeavors.

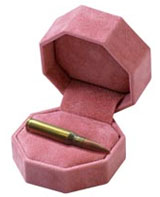

Specifically, I’ve been thinking about diamonds. Why, you ask? Well, because as I see more and more friends and family become engaged I have been seeing more and more diamonds. To be clear, I have not become pre-occupied with the idea of engagements and rings, but with the desire for diamonds in particular. I’ve been trying to understand just what it is that makes them so desirable, given that we all know, on some level, that the market demand for these stones fuels violent conflict, war and suffering in many places of the world. That is the connection that I aim to tease out.

A caveat: I have many friends and family members who own diamonds and covet them. In fact, I, too, find them quite beautiful, as a self-professed lover of shiny, beautiful baubles. I possess one pair of diamond earrings that belonged to my Nani (grandmother) in India and were given to me by mother after Nani passed. I love those earrings, and wear them rarely, with a mixture of both sorrow and joy. When I see diamond rings, earrings and necklaces on others, I admire their beauty. Increasingly, though, I find it very hard to un-remember the social ramifications of our cultural desire to give/own/receive diamonds as declarations of love and affection. Especially, when I think of the wars that these beautiful objects make us complicit in.

In specific regard to engagements: others have argued about whether or not they are an outmoded social custom. Quite honestly, I believe in living and letting live on this issue. I’m not here to be the crunk feminist betrothal police. I certainly, have my own opinion about engagements (I’m down) and weddings (it’s complicated) and the relation of all these things to romantic love (perhaps a forthcoming blog-post?).

In specific regard to engagements: others have argued about whether or not they are an outmoded social custom. Quite honestly, I believe in living and letting live on this issue. I’m not here to be the crunk feminist betrothal police. I certainly, have my own opinion about engagements (I’m down) and weddings (it’s complicated) and the relation of all these things to romantic love (perhaps a forthcoming blog-post?).

A smidgen of history: The “tradition” of the diamond engagement ring is actually rather new. The first known diamond engagement ring was commissioned for Mary of Burgundy by the Archduke Maximilian of Austria in 1477. Then, in the late 19th century, mines were discovered in South Africa, driving down the price of diamonds. After which, Americans regularly began to give (or receive) diamond engagement rings. Before this moment, some women got thimbles instead of rings to signal their betrothal.

Now here’s the clincher (from a great piece by Meghan O’Rourke in Slate):

“Even then, the real blingfest didn’t get going until the 1930s, when—dim the lights, strike up the violins, and cue entrance—the De Beers diamond company decided it was time to take action against the American public.

In 1919, De Beers experienced a drop in diamond sales that lasted for two decades. So in the 1930s it turned to the firm N.W. Ayer to devise a national advertising campaign—still relatively rare at the time—to promote its diamonds. Ayer convinced Hollywood actresses to wear diamond rings in public, and, according to Edward Jay Epstein in The Rise and Fall of the Diamond, encouraged fashion designers to discuss the new “trend” toward diamond rings. Between 1938 and 1941, diamond sales went up 55 percent. By 1945 an average bride, one source reported, wore “a brilliant diamond engagement ring and a wedding ring to match in design.” The capstone to it all came in 1947, when Frances Gerety—a female copywriter, who, as it happened, never married—wrote the line “A Diamond Is Forever.” The company blazoned it over the image of happy young newlyweds on their honeymoon. The sale of diamond engagement rings continued to rise in the 1950s, and the marriage between romance and commerce that would characterize the American wedding for the next half-century was cemented. By 1965, 80 percent of American women had diamond engagement rings.”

[For an interesting demonstration of cultural production, please see the DeBeer’s Website for their version of the history of the engagement ring.]

So, in light of all this, let’s return to the central question: what exactly is a conflict diamond?

“Conflict diamonds are diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the decisions of the Security Council.”

According to the NGO, Global Witness, conflict diamonds have funded brutal conflicts in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo and Côte d’Ivoire. These conflicts have resulted in the death and displacement of millions of people. Diamonds have also been used by terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda to finance their activities and for money-laundering purposes.

Brought into the mainstream by the film Blood Diamond, which featured Hollywood heavyweights like Leonardo DiCaprio, Djimon Hounsou and Jennifer Connelly, there has been some attention drawn to conflict diamonds and the long standing movement to curb and eliminate their production.

In 1998, Global Witness (which was co-nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for this work) launched a campaign to expose the role of diamonds in funding conflict, as part of broader research into the link between natural resources and conflict. In response to growing international pressure from such NGOs, the major diamond trading and producing countries, representatives of the diamond industry, and NGOs met in Kimberley, South Africa to determine how to tackle the blood diamond problem. The meeting, hosted by the South African government, was the start of a complicated and fraught three-year negotiating process, which culminated in the establishment of an international diamond certification scheme. The Kimberley Process was launched in 2003, and endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Security Council. According to NGO’s like Global Witness, who are monitoring and evaluating the Kimberly Process it’s clear that diamonds are still fueling violence and human rights abuses. Although the Process makes it more difficult for diamonds from rebel-held areas to reach international markets, there are still significant weaknesses in the scheme that undermine its effectiveness and allow the trade in blood diamonds to continue.

Knowing this, here’s why I decided to research and write this post: we can actually stop this. Diamonds are not food. Diamonds are not required for survival. A change in cultural attitudes can actually stop these conflicts. It can stop the violence in communities where these diamonds are found. If the desire for diamonds were to vanish, these conflicts would lose exactly what fuels them.

I don’t write this post to make people with diamonds on their fingers feel bad. I shop for bargain goods that I know are made in sweatshops. When I purchase produce, I know that it was grown and picked by laborers whose rights are violated. I try to make ethical choices, all while knowing that I am complicit in a world economy that is rooted in human rights violations.

This is the beautiful thing about symbols, they can be changed. They have only as much power as we give them. We can actually stop much, if not all, of the violence that is a result of the demand for diamonds. They way that our cultural attitudes about buying fur have changed within a generation, so can our cultural attitudes about diamonds, I propose. It’s not really going to be easy, they are a beautiful and powerful symbol of wealth and status. Increasingly, I hear many politically conscious people say they want a “vintage” diamond. This is clearly an effort towards detangling oneself from the trade of conflict diamonds. My point here, though, is about the cultural cache of diamonds. While purchasing a vintage one might not support the blood diamond industry directly, it certainly does nothing to challenge the value that diamonds have in our society.

All that being said, I think we can indeed move the needle.

“Diamonds are forever” it is often said. But lives are not. We must spare people the ordeal of war, mutilations and death for the sake of conflict diamonds.” – Martin Chungong Ayafor, Chairman of the Sierra Leone Panel of Experts

However, eventually, I think we can change the way we think about diamonds. If we know more, and if we are challenged to face the truth about the havoc they wreak, we might make different choices. We might not choose diamonds after all. They have nothing to do with love, as it turns out.

My best friend sent me your post. I would just like to say THANK YOU! My husband and I decided against a diamond engagement ring. We actually decided against a “conflict-free” engagement ring as we felt that the issue is indeed desire. By wearing a diamond ring–conflict or conflict-free–we were still fueling the desire for a diamond ring for my younger cousins, friend’s kids, our own future children, etc. In lieu of a diamond ring, we built a school through the charity Free the Children in the Kono District of Sierra Leone, Africa, site of the diamond wars in the country. It was our engagement gift to one another. I really wish more people thought about this deeply disturbing issue. A beautiful and intelligent piece that I hope is read by many.

Many thanks and Blessed Be¡

When my husband and I decided to get engaged, I was vehemently opposed to a diamond ring. We both felt ethically opposed to it, and we didn’t feel like it represented our transnational, multiracial relationship. We settled on a beautiful blue-topaz ring (my birthstone) on a white-gold band. But when we would show people my ring, there was always surprise, awkwardness and questions: it’s like our commitment was somehow less valid because we hadn’t put down 3000$ on a diamond. For heaven’s sake, it’s an AD CAMPAIGN! It’s hard because the invalidation and subtle judgement wears you out; thank you for this post, and for a much-needed slice of validation.

My husband bought me a gorgeous, lab-made ruby engagement ring. The first words out of his mom’s mouth when she saw it? “THAT’S not a diamond!” People also assumed that he couldn’t afford a “real” engagement ring. I don’t even really like diamonds. I think a lot of people saw it as a criticism of their own choices.

I feel the same way about diamonds. My husband and I chose moissanite as an alternative to diamonds in our wedding sets, and we couldn’t be happier with the decision – monetarily, ethically, and aesthetically.

I love this post! Thanks for spreading the word!

I like that you focused on the embedded need for a diamond ring rather than preach about buying conflict-free products. It really is important to realize how consumerism has co-opted love, something that’s supposed to be a pure emotion. I think its fantastic that we have the Kimberley Process but let’s talk about computers and cellphones. Of all products that are rooted in human rights violations, technology is the least talked about (google coltan + conflict). I’m typing this on a product which probably caused the death of thousands if not more. At least with diamonds, clothing and food, we have an alternative but where is our technological alternative?

This is a great question. Technology is a source of liberation and power for many folks, yet the horrific circumstances of it’s production are almost never addressed. I’ve made a commitment to only purchase re-furbished products, but I don’t think that’s sufficient. I don’t know the answer here, but the question is certainly going to get me to do more research about what I purchase and why.

Thanks for this post. I hate diamonds simply because I was in South African and went to the Kimberley diamond minds and while I was in RSA I saw people who were debilitated from having worked in the mines. My partner and I went a different route when we got married like many of the other commenters.

This post got me thinking about marriage, rings, and heterosexuality because while many times we can assert loudly that we are progressive on the rings the heterosexist foundation upon which the symbolic exchange is premised needs more discussion. The fact that all the comments indicated that the husband was responsible for getting the rings, the fact that there are no queer representations of marriage rituals and symbols, and the fact that there needs to be a revision of what is being exchanged in marriage suggests to me that there is so much more to this discussion than I think the commenters are engaging in. The hard part for me is that narrow notions of “white femininity” advertised globally continue to be balanced on the backs of African people as long as diamonds are central for engagements for all women.

On the flip side, my understanding of why women (particularly what black women have told me) want the ring is for the literal promise of security. If the marriage doesn’t work then the woman knows she has a down payment on a new life as a divorcee. We don’t really talk about the ring as money cause that f*cks up the fantasy, but for my friend who went through a nasty divorce, that ring paid rent and utilities for a good many months until she got on her feet. I’m just saying maybe we could cut out the middle man and have the “breadwinner,” if there is such a thing, put several thousand dollars in an account (or start a payment plan) in your name and if the marriage works then you have a nest egg and if it doesn’t you have options. In an ideal situation, without income inequality, two (or more) people could simply exchange vows to be vulnerable enough to grow, learn, support, raise children (or not), love and be loved for as long as they both (all) shall want.

But for right now my true self says-Diamonds Suck! for a variety of reasons so please diamond lovers consider other options.

Sheri, thanks for bringing up the deeper connections to heteropatriarchy at play here. This point really shows us just how seamlessly diamonds were tied to financial security.

Historically, until the 1930s, a woman jilted by her fiance could sue for financial compensation for “damage” to her reputation under what was known as the “Breach of Promise to Marry” action.

Eventually, courts began to abolish these actions, and DeBeer’s really capitalized on this legal trend by pitching diamonds as NOT JUST a symbol of love but also a financial commitment. In some ways, this is a major factor as to why women became so invested in having a diamond. It was about status, yes, but it was also security,

Another important twist, in the historical context that Meghan O’Rourke from Slate discovered in her piece: in the 1930’s to be marriageable, a woman needed to be a virgin, but many women of the time lost their virginity while engaged. So here enter diamonds, again, to save the day (GAH) because some structure of commitment was necessary to assure engaged women that men weren’t just trying to get them into bed. The “Breach of Promise” laws had helped society seemingly prevent all the guys from seducing, bedding and then leaving women; as those laws went out the window, a really expensive engagement ring would do the same.

Anyhow, yes! Great point, and a complicated history. And I think your challenge about thinking creatively in a sexist society about what security means in an engagement/marriage context is SO SO important. No easy answers, but I’m grateful for the questions.

amen to everything sheridf said (heyyy, girl!)

it’s not uncommon for people to adopt the (typically lazy) argument that “a lot of products i buy are harvested/manufactured/etc in suspect ways…why should i give up this one?!?!” the post’s author made a critical point in answering: we have the power to dismantle the mythology of the diamond engagement ring (and, to a lesser extent, the diamond cartel it benefits) because the diamond engagement ring derives from our emotional investment in it.

Brilliant post. This is such an important and unpopular topic. I try very hard not to be judgmental, but it is shocking to me how many otherwise progressive friends want and receive diamond rings. I even have a friend who wrote a story about the stigma couples face when they get engaged without putting a ring on it. De Beers’ role in pimping the tradition is not publicized enough. If it were, I think more bobos who wouldn’t be caught dead eating in McDonald’s or tossing out a recyclable bottle would feel the same shame in sporting rocks. Even conflict free diamonds are symbols linked to conflict. A related ethical dilemma is that De Beers now funds HIV/AIDS and women’s health projects and organizations. I went to a gala hosted by a feminist organization a few years ago and was surprised to find De Beers reps on the program, as they had underwritten the costs for the entire event. On the one hand, I understand that money is money. On the other hand, it felt like this organization was helping to cleanse the company’s tainted image by allowing them to promote their name alongside the nonprofit’s work. Not one but two diamond company spokespersons gave presentations over the course of the evening.

Ack, Leila. I did not know about DeBeers’ philanthropic efforts. In this case, it seems to be pretty directly about rehabilitating the image so that it doesn’t get in the way of diamond sales. I find corporate funders complicated for this very reason, but that said, accountability is really powerful. A PR campaign made DeBeer’s successful, and if it comes to it, a PR campaign (this time against them and their complicity in blood diamond trafficking) coupled with a changed cultural context around diamonds, is really the only thing that might be effective. But, man, that is a tough spot in re: getting and needing funds for HIV/AIDS work in Africa.

Thanks so much for this piece! It’s a really important conversation to have, though not an easy one.

Even more troubling for me than the (relatively recent) tradition of the diamond engagement ring is the (even more recent) phenom of the “right-hand ring” — diamonds meant to symbolize women’s self-love and economic independence. It was another De Beers campaign — this time a post-feminist celebration of the American Woman’s supposed freedom to, in the words of Destiny’s Child, “buy my own diamonds … buy my own rings” — that popularized the right-hand ring and created a whole new market for diamonds. According to Felicia Henderson, the De Beers campaign specifically targeted unmarried Black women (she has a section on the right-hand ring in “Single, Successful, and Othered: Media and the ‘Plight’ of Single Black Women”).

Since then, the diamond industry has worked hard in the U.S. to attach the “right-hand ring” to Black & Latina celebrities and celebrity charity (see link below), and to create a new image of the diamond industry as a global good guy associated with post-racial female empowerment and international philanthropy, rather than the brutality and violence of the global diamond trade. (If Beyonce says South African diamond mines are okay, they must be!)

Selling diamonds in the name of heteronormative romance is bad enough. Selling diamonds as a symbol of Black women’s liberation is just megafucked.

LINKS: http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Beyonce,+Jennifer+Lopez,+and+Patricia+Arquette+'Raise+Their+Right…-a0158228816 (right-hand ring campaign & African charity)

http://www.genderacrossborders.com/2011/09/16/why-diamonds-aren’t-all-girls’-best-friends/ (info about women in diamond mining)

Thanks for the Felicia Henderson reference. I will check it out because it could be a good teaching tool.

excellent post. when i was thinking about what i wanted in an engagement ring (back before i met my wife), i didn’t necessarily want a diamond. i thought other gemstones were much more beautiful. i ended up with a diamond ring, but it was a vintage one that has been in her family for a few generations. because of that, my wedding band has diamonds on it too. we did make the choice to buy from brilliant earth, which uses canadian diamonds (i think) and reclaimed metals. i wouldn’t trade my beautiful, meaningful ring for the world, but i do 100% agree with trying to change the meaning of diamonds and get more people thinking about making their own traditions, instead of relying on advertising/peer pressure.

To add to your excellent piece, diamonds are not rare. It is my understanding that DeBeers keeps supply low in order to maintain price levels. They own the vast majority of legal diamond mines. There are also allegations of tampering with what little competition there is. If diamonds did not have value, so called blood diamonds would not exist.

I’m posting just to echo other commenters’ appreciation for this post, and to add thanks to the commenters for enriching the discussion. I’ve bookmarked this post and comments to include next time I teach Cultural Studies (too late for this quarter) and in some of my Women’s Studies courses as well.

1,100 women are raped each day in the DRC by armed groups which generate over $180million/year in trading conflict minerals used in the manufacture of our everyday electronics products and use rape as their chosen weapon of war just as the armed groups in Sierra Leone used the amputation of limbs. The U.N has called the DRC the Rape Capital of the World. Just thought this might be relevant to you or your classes: http://depauwcfci.org/

Love this….particularly am appreciative of the learning how this obsession is the direct result of a marketing campaign. The “American Dream” was a Madison Avenue creation of the 50s as well….makes me wonder how it was all tied in together.

Great post. Would you be willing to spreading the word about conflict electronics too?